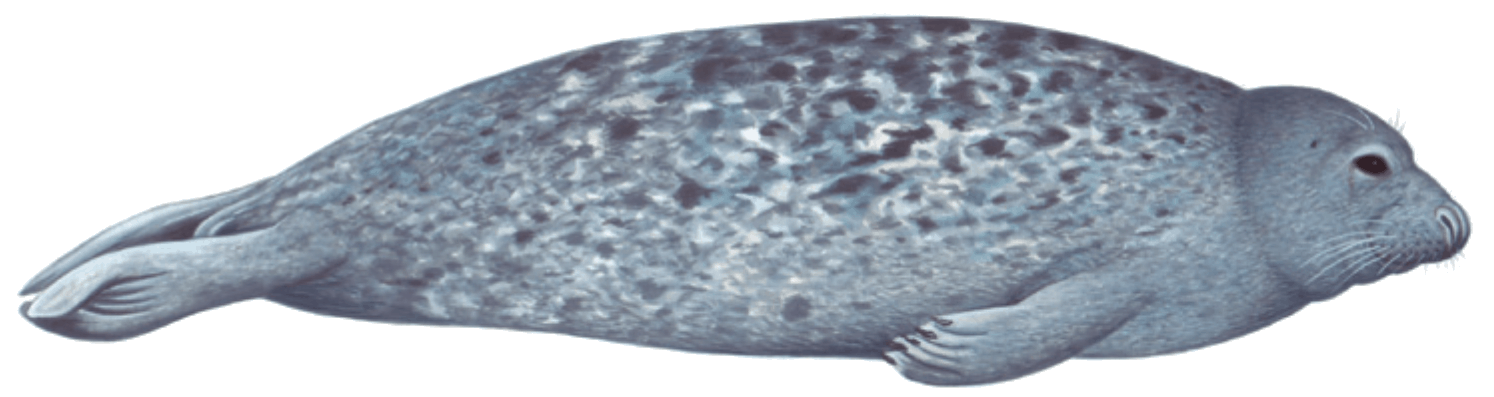

Pups are born with a long white fur coat (lanugo) that they moult out of by the time they are three weeks old into their shorter grey fur coat, which can vary from mottled pale to dark grey, brown, black and white. Males tend to be darker in colour and are mottled mainly around the neck. Females are most often mottled from their head along most of their body, being pale grey/white underneath and dark grey on top. Mature males will develop a longer, pronounced ‘Roman’ nose that also helps distinguish the sexes, as mature females retain the shorter, more concave profile from the forehead to the nostrils.The general appearance of the head of both sexes is more doglike compared to common seals. When closed, the nostrils of this species are parallel to each other.

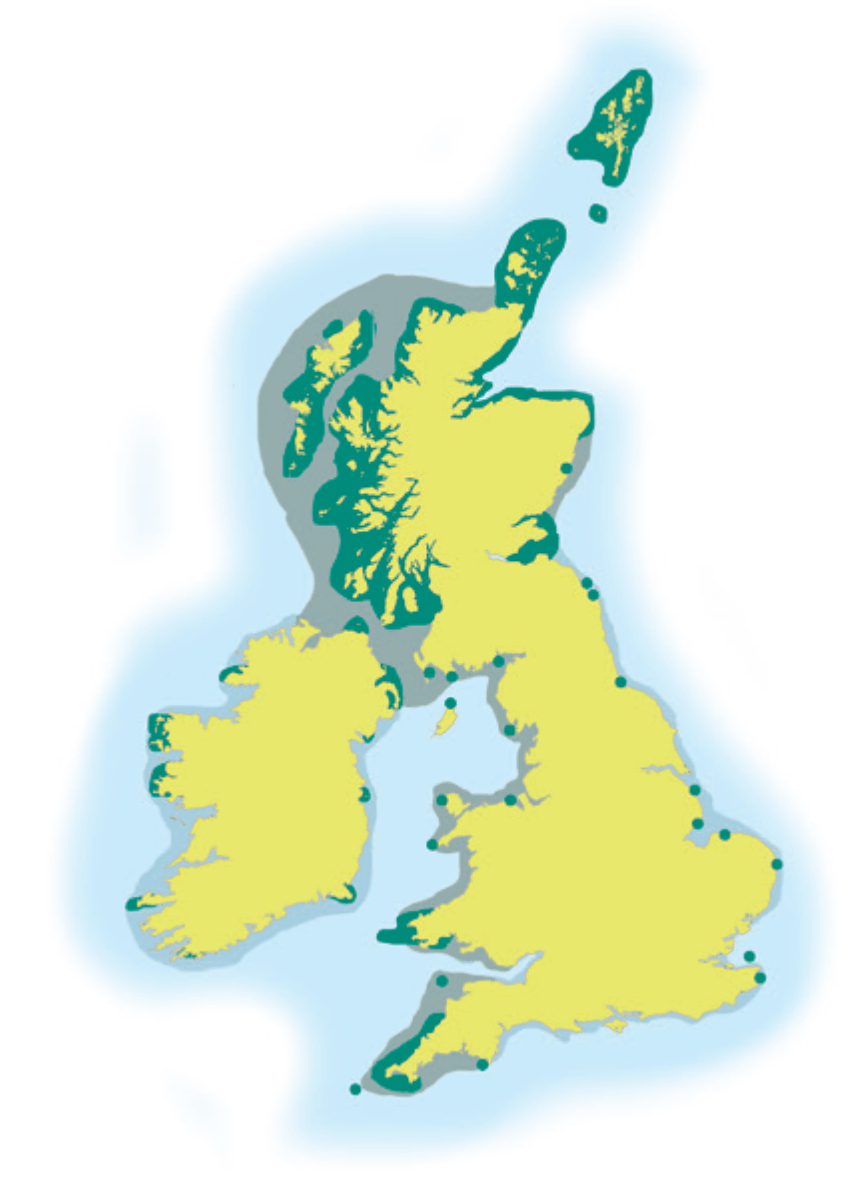

This species is found only in the North Atlantic Ocean, North Sea and Baltic Sea. With a grey seal population of 116,500- 167,100 (based on pup production – SCOS Report, Sea Mammal Research Unit 2016) the UK is the primary stronghold for approximately 38% of the global population. Colonies are found around Scotland (Inner and Outer Hebrides, Shetland, Orkney, Moray Firth to the Firth of Forth, Isle of May); North East England (Farne Islands, Northumberland, Yorkshire), with a few other significant colonies further South (Lincolnshire, Norfolk). Plus there are more, mostly smaller, colonies across Northern Ireland, Isle of Man, North West England (Cumbria), Wales (Bardsey Island, Skomer, Ramsey Island, Cardigan Bay, Pembrokeshire), South West England (Lundy Island, Devon, Cornwall, Isles of Scilly) and the Channel Islands, with a more small groups along the English Channel coast.

Grey seal pups tend to be rescued close to colony populations (see map in where to see them).

Adult seals are large powerful animals are are best left to trained and experienced medics.

Watch it from a distance. Do not approach the animal. Seals regularly haul out on our coasts – it is part of their normal behaviour and in fact they spend more time out of the water, digesting their food and resting. Therefore, finding a seal on the beach does not mean there is necessarily a problem and they should not be chased back into the sea as this may stop them from doing what they need to do – rest. A healthy seal should be left well alone.

After stormy weather and / or high tides, seals will haul out onto beaches to rest and regain their strength. Many do not need first aid, but we will always try to find someone to check them out just in case.

However, if there is a problem, there are a number of things you may see:

If you see a seal that may be abandoned, thin or ill, then call for advice and assistance:

BDMLR RESCUE HOTLINE:

01825 765546 (24hr)

or

RSPCA hotline (England & Wales): 0300 1234 999

SSPCA hotline (Scotland): 03000 999 999

You will receive further advice over the phone. If there is a problem with the animal, there are some important things you can do to help:

If you find a dead seal

The Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) collects a wide range of data on each stranding found on English and Welsh shores, whilst the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS) does the same for Scotland. If you discover a dead animal, please contact the relevant hotline and give a description of the following where possible:

Digital images are extremely helpful to identify to species, as well as ascertaining whether the body may be suitable for post-mortem examination.

CSIP has produced a useful leaflet that can be downloaded by clicking here.

CSIP hotline (England and Wales): 0800 6520333.

SMASS hotline (Scotland): 07979 245893.