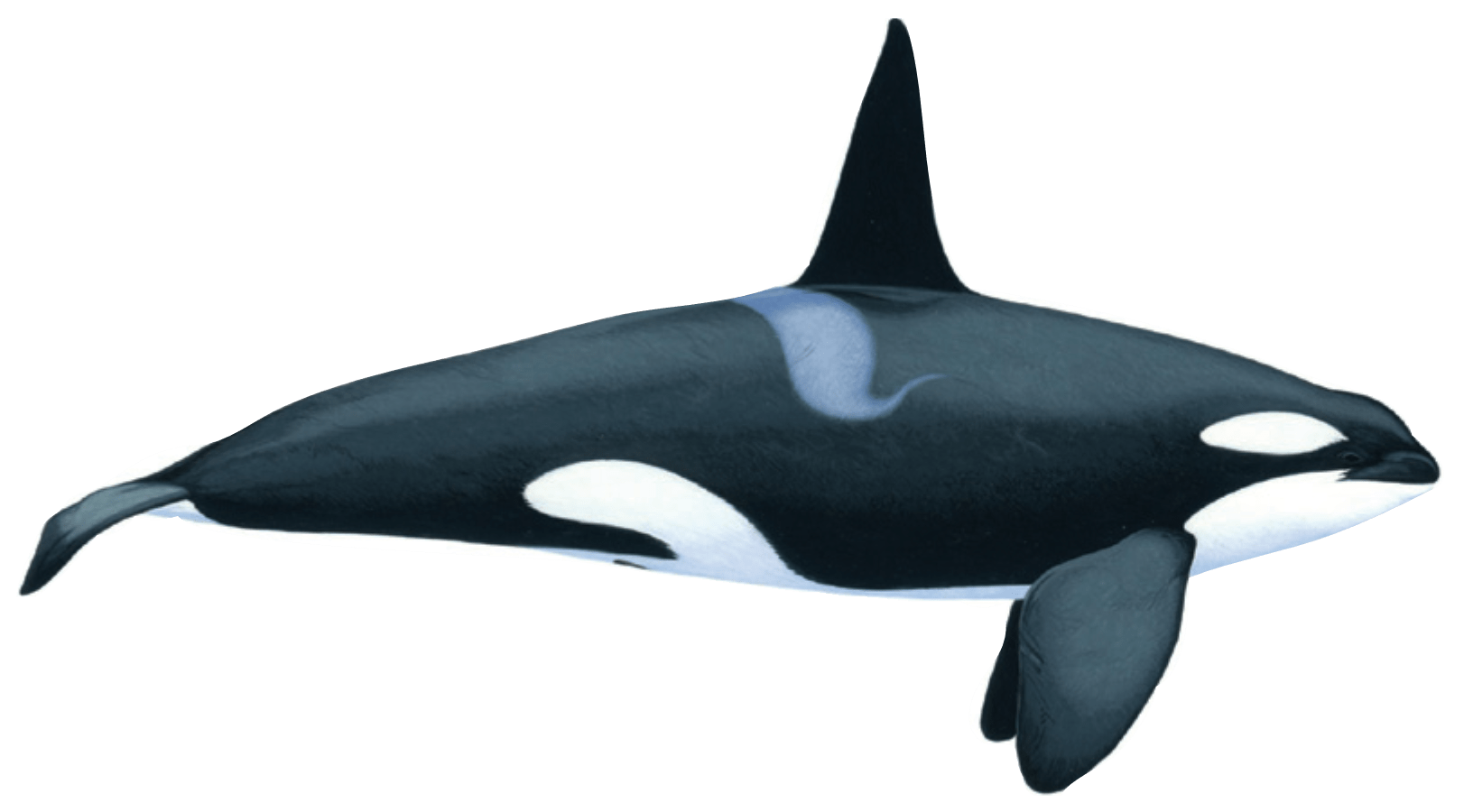

A coastal or pelagic species measuring up to 9.8 metres in length, white ventrally with characteristic white markings on the sides, throat, chin and eye, on a black background, tall straight (in males) or curved (in females and juveniles) dorsal fin and no ‘beak’.

Killer whales have a gestation period of 16 to 17 months, calves are born at any time of the year, measuring 2.0 to 2.5 metres, and are around 4 metres in length when weaned. The species lives in stable groups of 3 to 50 and feeds on squid, fish and marine mammals.

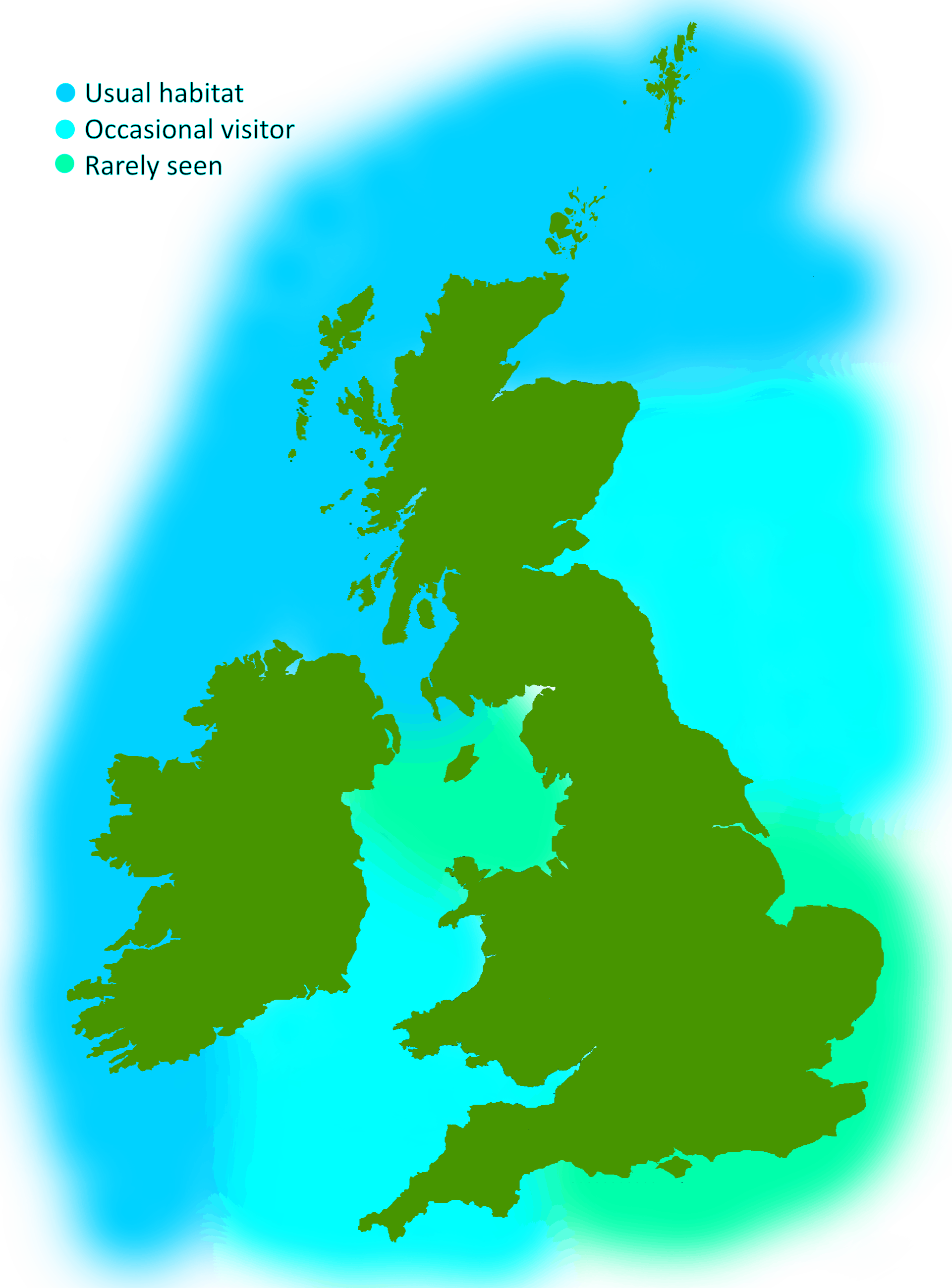

This species is widely distributed on the Atlantic seaboard, being mainly seen off northern Scotland, and occasionally off the Atlantic coasts of Britain and Ireland in the summer months.

The UK has one small pod that are entirely resident in our waters, usually referred to as the West Coast pod. Sadly this group has not produced a calf in over 25 years, and recent research on samples taken from a deceased individual showed it to have extremely high levels of a chemical pollutant called polychlorinated biphenyls, which have been associated with suppressing immune systems and reducing fertility. These chemicals were banned in the 1980s due to their toxicity, but take a very long time to break down, and as such are still leaching into the environment from places like landfills where they have not been disposed of properly, so continue to affect wildlife in the present. In all likelihood we will see the extinction of our only resident orcas as a result.

There are semi-resident pods that also visit the UK as well as transient animals that pass through on occasion, so they won’t disappear entirely.

Live strandings of this species are very rare in the UK. Similar to bottlenose dolphins, they are very savvy at navigating in inshore waters and it is very unusual for them to be caught out by tides and currents. Instead it is more often the case that they are very ill, injured or even reaching the end of their natural life.

An orca that live stranded in Kent in 1995 was the first major live stranding incident attended by BDMLR. Although it refloated on the tide, it was not in good condition and unsurprisingly restranded dead the following day.

A whale, dolphin or porpoise stranded on the beach is obviously not a usual phenomenon. These animals do not beach themselves under normal circumstances, and they will require assistance. Please DO NOT return them to the sea as they may need treatment and or a period of recovery before they are fit enough to swim strongly.

BDMLR RESCUE HOTLINE:

01825 765546 (24hr)

or

RSPCA hotline (England & Wales): 0300 1234 999

SSPCA hotline (Scotland): 03000 999 999

You will receive further advice over the phone, but important things you can do to help are:

If you find a dead cetacean

The Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) collects a wide range of data on each stranding found on English and Welsh shores, whilst the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS) does the same for Scotland. If you discover a dead animal, please contact the relevant hotline and give a description of the following where possible:

Digital images are extremely helpful to identify to species, as well as ascertaining whether the body may be suitable for post-mortem examination.

CSIP has produced a useful leaflet that can be downloaded by clicking here.

CSIP hotline (England and Wales): 0800 6520333.

SMASS hotline (Scotland): 07979245893.