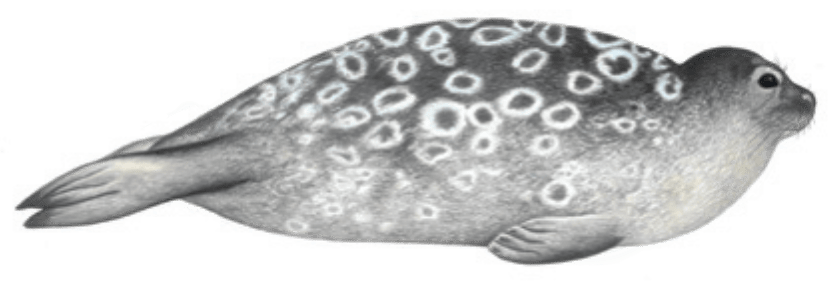

The ringed seal is named for the irregular ring patterns on its fur, which is mottled black/grey/white in colour. They are among the smallest of the seal species and there is little difference between males and females. They can be easily confused with common seals, but have a more robust body shape around the thorax, have a more obvious ring pattern on their fur and can also be more actively aggressive when approached. There are five subspecies and their overall range is throughout the Arctic Ocean, including Alaska (USA), North and East Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway and Russia, plus the Northernmost Baltic Sea around Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Sweden. The overall population is estimated to be around 3 million animals.

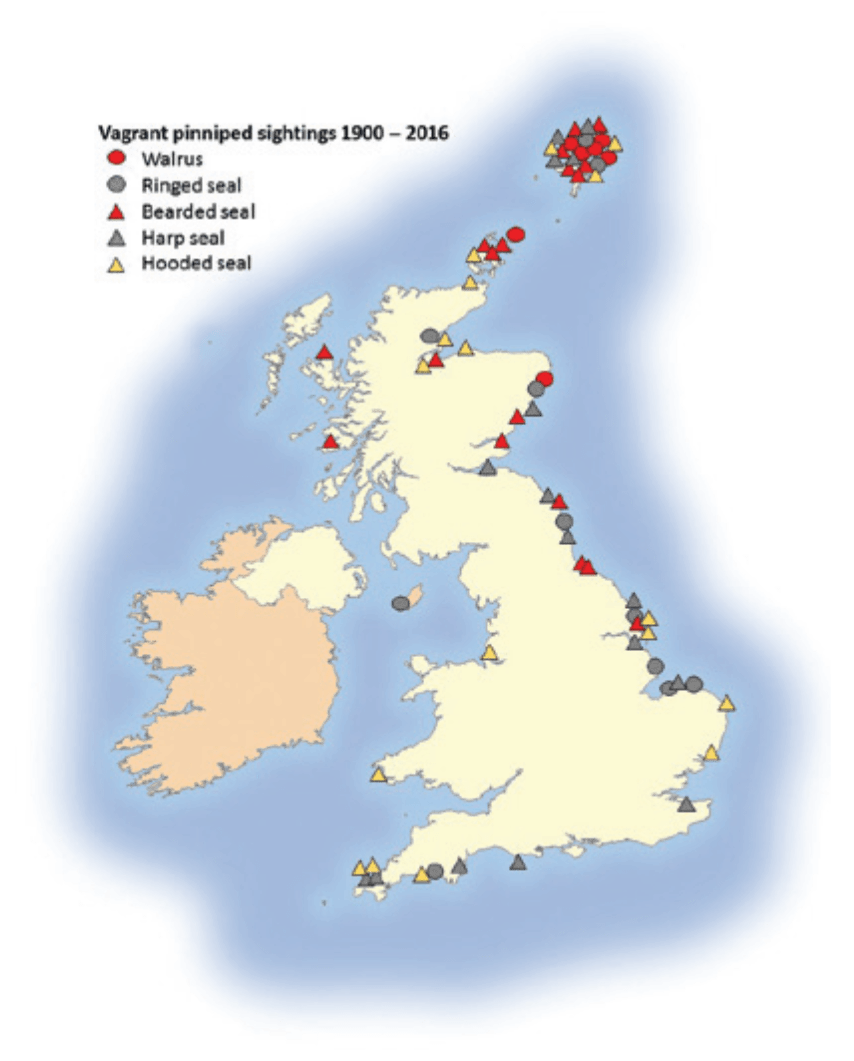

Ringed seals are extremely rare visitors to the UK as the species prefers the colder waters of the Arctic.

They have been found around the UK occasionally, particularly around Shetland and along the East coast.

Individuals found in the UK tend to be adults and not necessarily requiring rescue. As with most vagrant species most animals simply require monitoring and stay in an area for just a short time. There are plenty of food sources available and they are quite capable of surviving here.

Watch it from a distance. Do not approach the animal. Seals regularly haul out on our coasts – it is part of their normal behaviour and in fact they spend more time out of the water, digesting their food and resting. Therefore, finding a seal on the beach does not mean there is necessarily a problem and they should not be chased back into the sea as this may stop them from doing what they need to do – rest. A healthy seal should be left well alone.

After stormy weather and / or high tides, seals will haul out onto beaches to rest and regain their strength. Many do not need first aid, but we will always try to find someone to check them out just in case.

However, if there is a problem, there are a number of things you may see:

If you see a seal that may be abandoned, thin or ill, then call for advice and assistance:

BDMLR RESCUE HOTLINE:

01825 765546 (24hr)

or

RSPCA hotline (England & Wales): 0300 1234 999

SSPCA hotline (Scotland): 03000 999 999

You will receive further advice over the phone. If there is a problem with the animal, there are some important things you can do to help:

If you find a dead seal

The Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) collects a wide range of data on each stranding found on English and Welsh shores, whilst the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS) does the same for Scotland. If you discover a dead animal, please contact the relevant hotline and give a description of the following where possible:

Digital images are extremely helpful to identify to species, as well as ascertaining whether the body may be suitable for post-mortem examination.

CSIP has produced a useful leaflet that can be downloaded by clicking here.

CSIP hotline (England and Wales): 0800 6520333.

SMASS hotline (Scotland): 07979245893.