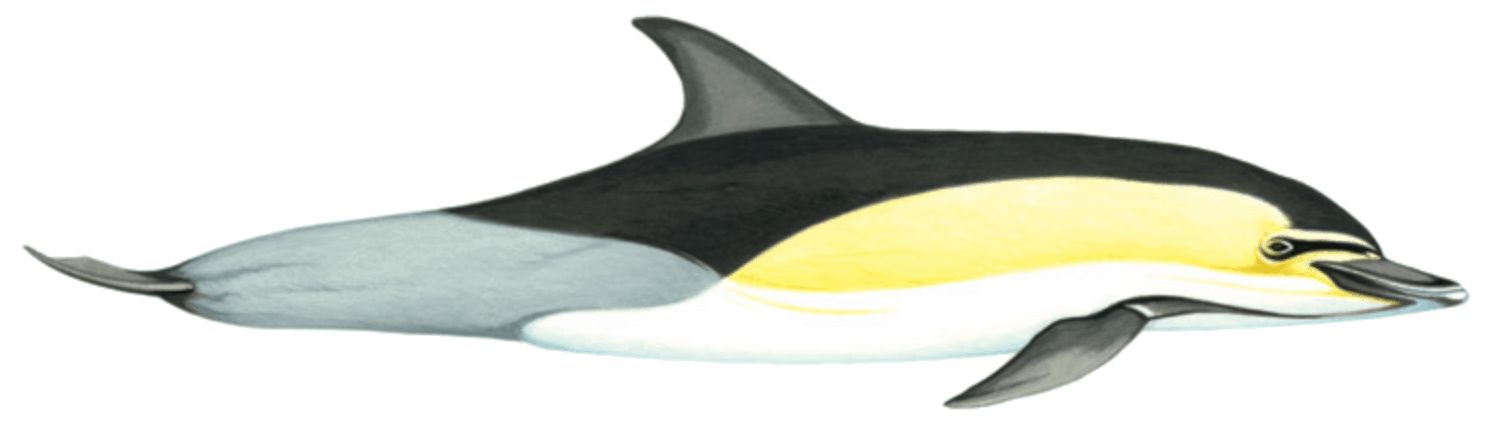

A pelagic species, measuring up to 2.5 metres, black/dark grey dorsally, white ventrally, with a characteristic ‘hour glass’ pattern along its flanks and a long ‘beak’ (rostrum). Common dolphins have a gestation period of 10 to 11 months, calves are born from spring to autumn, measuring 0.8 – 0.85 metres, are dependent for up to 19 months and are weaned at nearly 1.5 metres in length. The species is generally found in groups of 100+ in the Atlantic and they feed on fish, e.g. herring, sardines and pilchard, and squid.

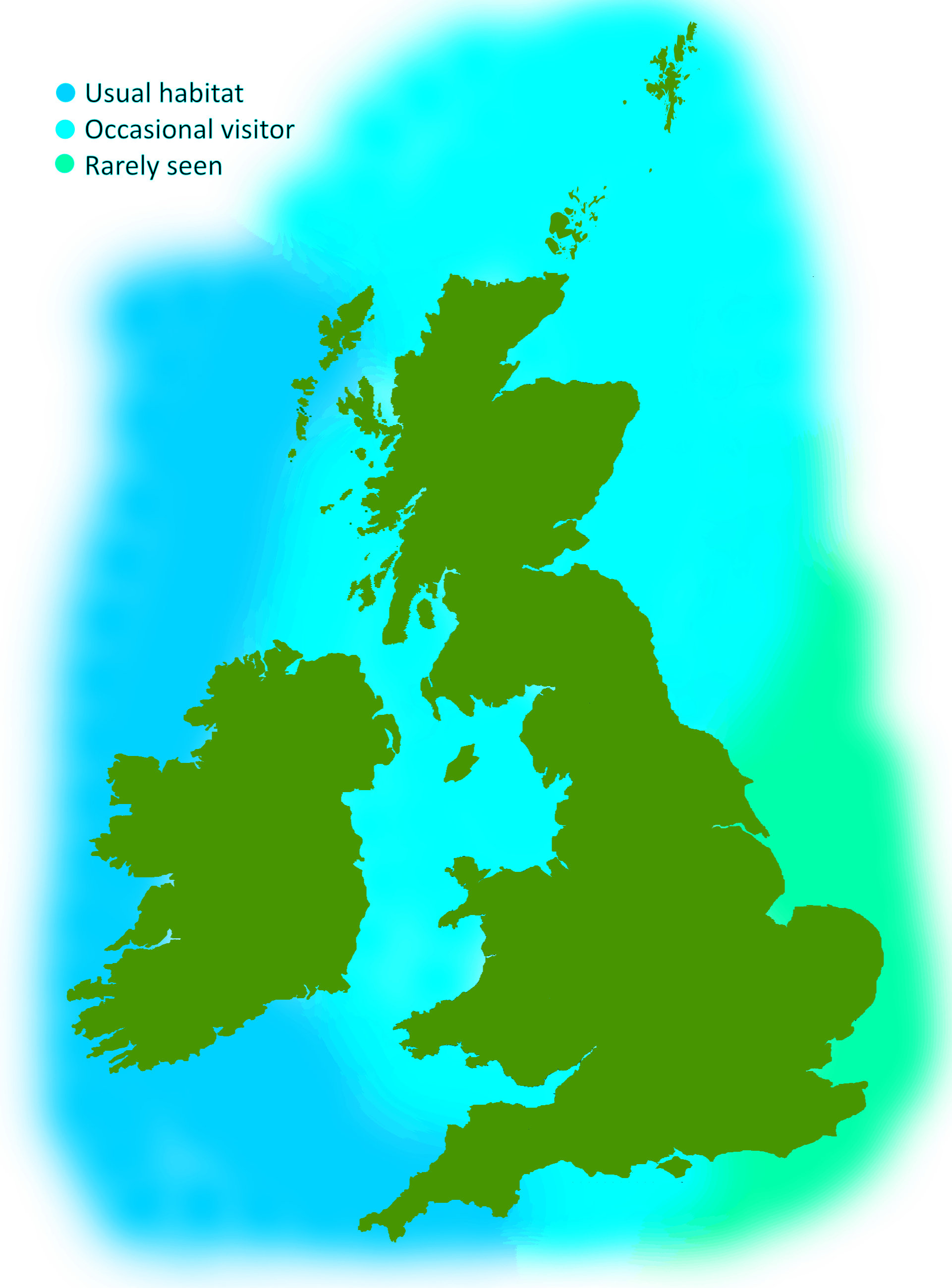

This species is frequently found in the western English Channel, off south west England, Ireland and in the Irish Sea. It is increasingly being reported around Scotland, possibly as a result of climate change and rising sea temperatures altering the distribution of species. Sometimes it is found in the North Sea and the eastern English Channel, but this is rare.

The species often travels in groups (sometimes numbering in the hundreds) and although primarily an oceanic species they can forage close to shorelines.

Common dolphins are one of the most frequently stranded cetacean species in the UK, just behind the harbour porpoise. They can become disoriented by channels, estuaries and tidal movements if close to shore though.

They are also one of the species most likely to mass strand. In June 2008 over 70 animals were rescued by the combined efforts of BDMLR and local emergency services in the Fal Estuary, Cornwall, while two others were put to sleep. A further 24 animals were already dead when found early in the morning though. The following investigation linked this incident, the largest common dolphin mass stranding on record for the UK, to a multinational military exercise that was ongoing in the area at the time, but since then BDMLR has developed a good working relationship with the Navy to respond quickly to incidents of this nature.

BDMLR’s success rate at refloating dolphins is good and as long as the animals are in a healthy condition, and especially if simply caught out by a tidal change or geographical feature.

A whale, dolphin or porpoise stranded on the beach is obviously not a usual phenomenon. These animals do not beach themselves under normal circumstances, and they will require assistance. Please DO NOT return them to the sea as they may need treatment and or a period of recovery before they are fit enough to swim strongly.

BDMLR RESCUE HOTLINE:

01825 765546 (24hr)

or

RSPCA hotline (England & Wales): 0300 1234 999

SSPCA hotline (Scotland): 03000 999 999

You will receive further advice over the phone, but important things you can do to help are:

If you find a dead cetacean

The Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) collects a wide range of data on each stranding found on English and Welsh shores, whilst the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS) does the same for Scotland. If you discover a dead animal, please contact the relevant hotline and give a description of the following where possible:

Digital images are extremely helpful to identify to species, as well as ascertaining whether the body may be suitable for post-mortem examination.

CSIP has produced a useful leaflet that can be downloaded by clicking here.

CSIP hotline (England and Wales): 0800 6520333.

SMASS hotline (Scotland): 07979245893.