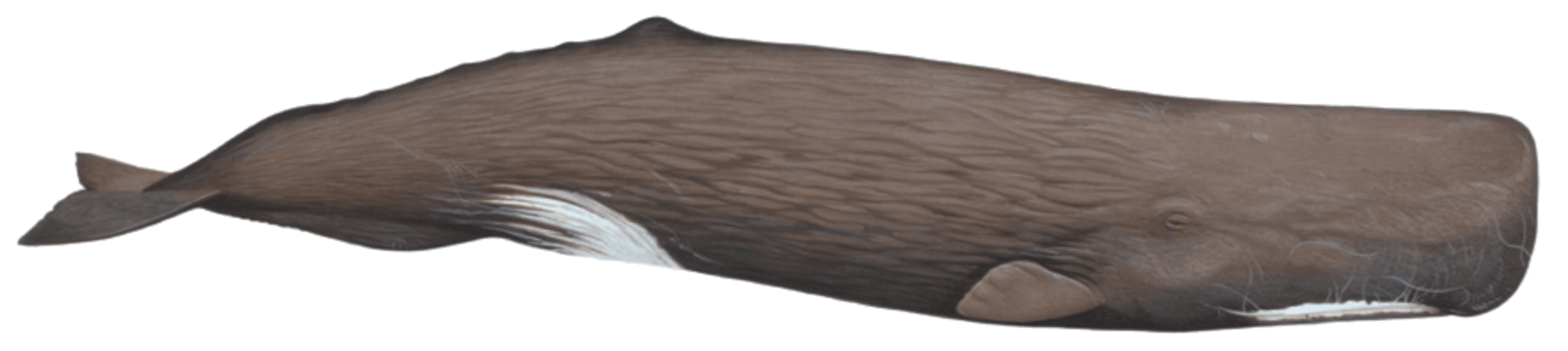

A pelagic species, measuring up to 20.5 metres in length, dark brown/grey in colour, with an elongated, rectangular head, a short lower jaw and no dorsal fin.

Sperm whales have a gestation period of 14.5 to 15 months, calves are born in summer and autumn, measuring 4.0 metres, and are dependent for up to 3.5 years. Females and calves are found in groups of 10 to 20 animals, but rarely venture above 45° North. Younger males are found in cooler water in variable sized bachelor groups, older males are generally solitary. The diet is nearly exclusively squid (and octopus), although in some areas fish are also taken.

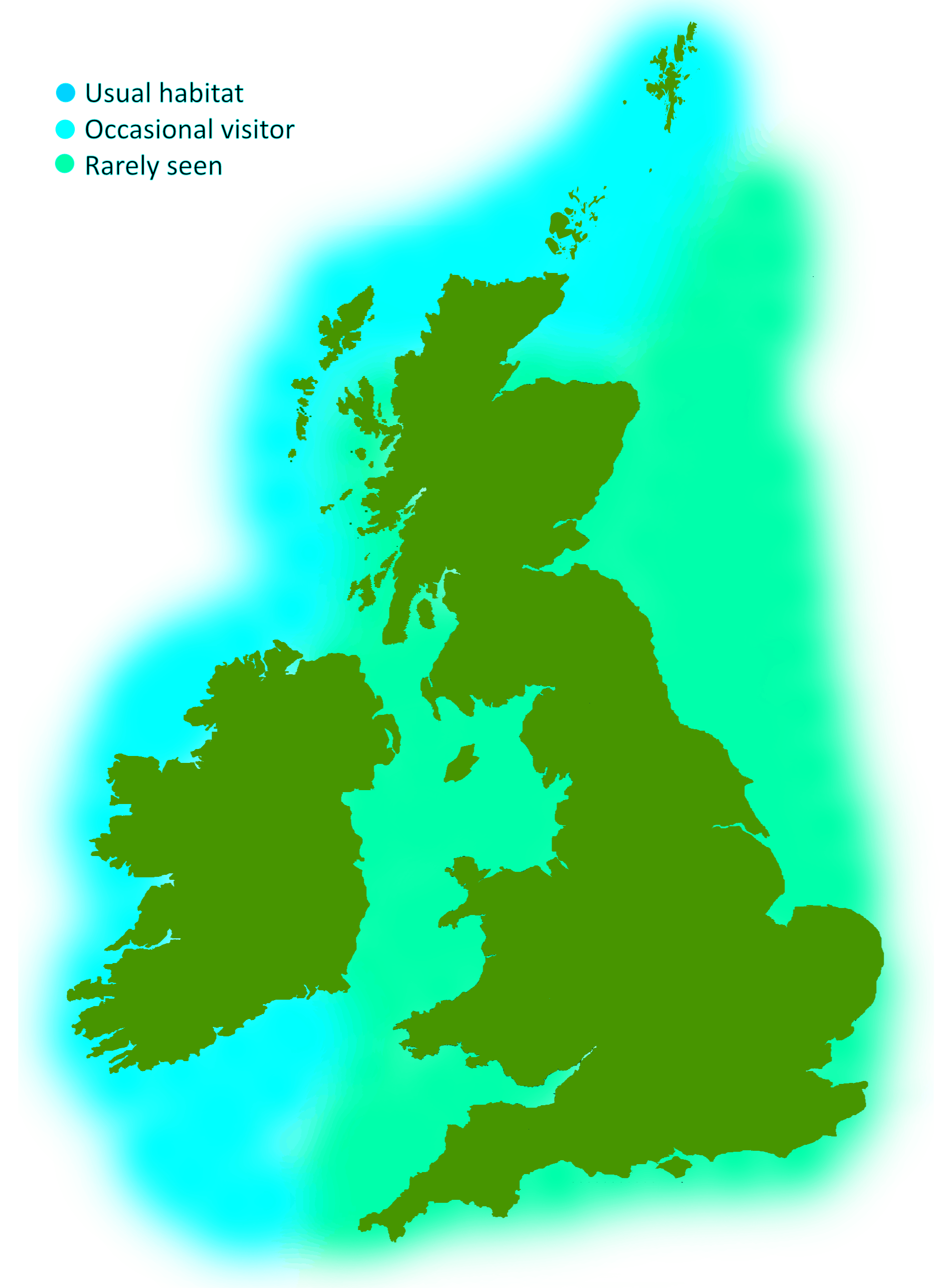

This species is found occasionally in the north Atlantic and is rarely seen in British coastal waters in late summer and autumn.

Females and juveniles tend to stay in the tropics all year, while males migrate north to cold temperate or even Arctic waters, passing the UK.

Sperm whales are a deep water species feeding on oceanic squid. Males spend the summer in the northern Atlantic and have been known to enter the North Sea in error, sometimes in bachelor pods of several animals. This leads to their health becoming compromised as they are so far from their normal habitat and they are unable to find their usual sources of food.

Often these animals will become stranded and are almost always in very poor condition by then, for which little can be done. They are so large and heavy that they can only be moved by the tide, so they cannot be transported.

Additionally, such large animals gradually crush themselves under their own huge weight, which they have never evolved to have to support out of water, meaning that refloating sperm whales is unviable in virtually all cases. If they are refloated by the tide and don’t restrand then they will almost certainly perish at sea.

A whale, dolphin or porpoise stranded on the beach is obviously not a usual phenomenon. These animals do not beach themselves under normal circumstances, and they will require assistance. Please DO NOT return them to the sea as they may need treatment and or a period of recovery before they are fit enough to swim strongly.

BDMLR RESCUE HOTLINE:

01825 765546 (24hr)

or

RSPCA hotline (England & Wales): 0300 1234 999

SSPCA hotline (Scotland): 03000 999 999

You will receive further advice over the phone, but important things you can do to help are:

If you find a dead cetacean

The Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) collects a wide range of data on each stranding found on English and Welsh shores, whilst the Scottish Marine Animal Strandings Scheme (SMASS) does the same for Scotland. If you discover a dead animal, please contact the relevant hotline and give a description of the following where possible:

Digital images are extremely helpful to identify to species, as well as ascertaining whether the body may be suitable for post-mortem examination.

CSIP has produced a useful leaflet that can be downloaded by clicking here.

CSIP hotline (England and Wales): 0800 6520333.

SMASS hotline (Scotland): 07979245893.